Voting is the bedrock of democracy, and it’s crucial to maintain its integrity. Otherwise, we might see a repeat of January 6, where a group of people distrusting existing systems may take violent means to secure the electoral integrity they imagined being robbed of.

Today, more than ever, the hoi polloi expect that the voting results are accurate and the entire process transparent and secure so that everyone is convinced about the genuineness of the elections.

And chances of anyone interfering with or preventing someone else’s vote from being counted shouldn’t arise.

But we don’t live in an ideal world, and we occasionally hear stories about how an entire election was marred by pre-poll rigging and intimidation.

However, with the advent of blockchain technology, many have begun to see it as a technology that guarantees the integrity of the voting process. And they do have a point, as this technology provides many benefits that the current voting system lacks.

For instance, everything that runs on a blockchain runs according to predetermined code that no one can tamper with or prevent from being executed. It is also not possible to censor or block any user's input from being processed on a blockchain.

Given these advantages, using blockchain for elections has gained serious attention in the past year. Countries like Estonia have even successfully implemented blockchain voting systems.

So what's the catch?

Well, despite their advantages, blockchains do have flaws that may raise potential challenges when trying to implement large-scale blockchain voting. In this post, I aim to discuss these challenges in detail and explore popular alternative blockchain voting systems. But first, let's dive into Estonia’s case to understand how blockchain voting can be implemented in a real-world scenario.

Estonia’s Success With Blockchain Voting

Estonia embraced blockchain technology to free its technology and telecommunication hardware from Russian spies.

It’s said that the country’s digital revolution began when the Estonians decided to get rid of the bronze statue at the Soviet war memorial in the bustling capital city of Tallinn due to their ongoing tension with Russia. The Russians didn’t like what happened and launched a massive cyber attack that disrupted the websites of national organizations ranging from political parties to banks and newspapers.

The Estonians were shocked and helpless as their entire nation was taken off the grid. But they vowed never again to be the victims of such a digital assault.

The country decided to eliminate every piece of technology and telecommunication hardware vulnerable to Russian spies. In 2008, Estonia was internally testing “hash-linked time stamping.” In 2012, the Estonian cryptographers created K.S.I., a scalable blockchain technology.

The new technology was meant to ensure data integrity and protect against insider threats. Whether hackers, system administrators, or even the government itself, no one can manipulate the data and get away with it. This made Estonia the first country to implement blockchain on a national level successfully.

But then, one thing that separated Estonia from other countries, which allowed the country to go full-throttle on blockchain voting, was that it was already a pioneer in electronic voting technology. 99% of services are online, and 100% of government data is stored on a blockchain ledger system. Whether it is E-Estonia healthcare, property, business, court systems, or even official state announcements, everything is digital.

Just because it worked for Estonia doesn’t mean that it is completely foolproof. While Estonia stands as a rare success story that the world can learn from, below, I share a few more stories that demonstrate the risks involved in blockchain voting.

The Vulnerabilities of Blockchain Voting Systems

It turns out that there are a good number of interesting stories on the internet that staunchly oppose the integration of blockchain technology and the electoral process.

Here are a few excerpts to give you a gist:

However, in this threat-filled environment, online voting endangers the very democracy the U.S. military is charged with protecting.

Source: Computerworld

This situation will not fly for government elections, where state and local authorities manage lists of eligible voters. Neither would most governments tolerate the possibility of a voter being disenfranchised if their digital voting key is swallowed by a damaged hard drive or stolen by a thief to cast a fraudulent vote.

Source: Scientificamerican

No, blockchain isn't the answer to our voting system woes.

Source: Cnet

Blockchain-based elections would be a disaster for democracy.

Source: Arstechnica

What good is it to vote conveniently on your phone if you obtain little or no assurance that your vote will be counted correctly, or at all?

Source: MIT

It can make ballot secrecy difficult or impossible.

Source: Schneier

One big reason for the relentless criticism Blockchain voting faces is that even Blockchain-based electronic voting systems can be hacked.

Here are two interesting stories that explore the vulnerabilities of blockchain further.

How Moscow's Ethereum-based Voting System was Cracked Open by a French Security Researcher in 20 Minutes

In 2020, Russian officials announced that the Moscow City Duma would use a blockchain voting system for its election. They wanted to have a fair and transparent election, which was most likely conducted to improve the government’s image in the eyes of the Russian people and the world at large. Russia has often been accused of not having free and fair elections ever since Vladimir Putin became President.

A few weeks before the election, the officials decided to test the system and offered a reward on GitHub. Anyone who successfully cracked the new voting system would be awarded $15,000.

Pierrick Gaudry, a French researcher from Lorraine University, was able to break the Ethereum-based smart contract encryption in just 20 minutes, using a basic computer and software. He didn't rely on sophisticated techniques or modern equipment, which, if he had, might have taken him only 10 minutes to hack the system then.

How West Virginia, the first US state to use a Blockchain-based Mobile Voting System, came under Fire from Technology Experts

Similarly, in 2018, West Virginia became the first US state to allow overseas voters to cast absentee ballots for midterm elections via a blockchain-enabled mobile application. Voatz, the company West Virginia worked with, claimed that 144 individuals from 31 countries successfully submitted ballots for the November election via their app. They even deployed their app in Denver, Oregon, and Utah elections.

So, how was the reception? Many technology experts have expressed their concerns about this application.

They felt there was an enormous potential for glitches and security risks on people's mobile devices, the networks that hosted them, and the servers that held their information. Many experts described West Virginia's experiment as follows:

"Horrible"

"Horrific"

"Completely nuts."

"High-flying blockchain promises."

"The Theranos of voting"

"Just No"

And researchers from MIT attested to them right when they identified many security vulnerabilities in the voting application. They reverse-engineered the app and created a model of Voatz's server.

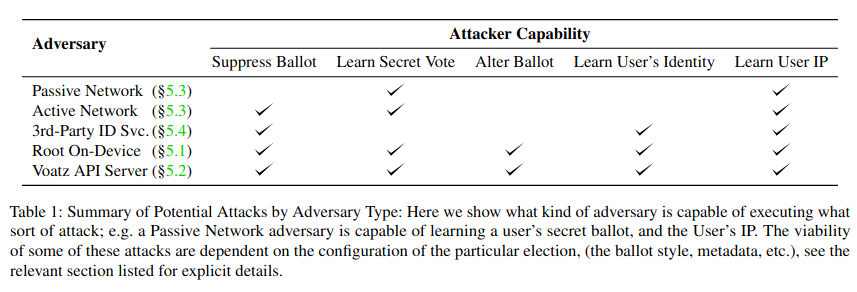

The researchers then found that an adversary with remote access to the device can alter or discover a user's vote and change those votes if the server is hacked. Also, the app's protocol does not attempt to verify genuine votes with the back-end blockchain.

Further investigation revealed that a passive network adversary, like an internet service provider or a stranger nearby if you are on public Wi-Fi, could detect which way you voted through some configuration. A more aggressive attacker could even detect which way you are going to vote and then stop the connection based on that alone.

Voatz's application also poses privacy issues for users. It uses external vendors for voter ID verification, so anyone can potentially access a voter's photo, driver's license data, or other forms of identification if that vendor's platform is not secure. Their privacy policy is vague and does not explicitly mention what kind of data they send to external vendors.

(Source)

The problem with Voatz's app was that its infrastructure was completely closed-source. Also, the people who built the application didn’t have the expertise to keep the voting process secure.

In general, the blockchain voting system as implemented by Votaz lacked transparency. For the sake of maintaining the integrity of elections, there is a need for more openness. If a part of the election is opaque, not viewable, not public, or has proprietary components, then that system is inherently suspicious and needs to be scrutinized.

All of this harms the credibility of the blockchain voting system, making it difficult for it to get normalized.

The cases mentioned above are instances of poor blockchain implementation that could have been avoided had the developers taken the necessary precautions.

Unfortunately, this may be the beginning of potential challenges that can spell doom for blockchain voting. Two major concerns surface when implementing wide-scale blockchain voting: lack of privacy and resistance to coercion.

Let's take a moment to understand these better and how, if at all, these concerns can be addressed.

Major Stumbling Blocks within the Blockchain Voting System

In the recipe for the perfect electoral voting system, there are four essential ingredients:

- Censorship resistance

- Immutable execution

- Privacy protection

- Coercion resistance

Censorship resistance refers to the system’s ability to ensure that everyone eligible to vote can vote, and immutable execution ensures that every vote gets counted correctly. These attributes are well preserved and fully supported in blockchain-based electoral voting systems.

Privacy refers to ensuring that the status and choice of one’s vote remain hidden, and coercion resistance is the ability to defend against external forces dictating a voter's choice. Blockchain voting, at least in its current implementation, has been heavily scrutinized for lacking these attributes. Let's take a deeper look at these to understand how.

Lack of Privacy And Coercion Resistance

Privacy protection can be a concern for blockchain voting because the digital infrastructure deployed to facilitate blockchain-based electoral voting can always be hacked. However, coercion resistance is the greater of the two concerns.

We need coercion resistance to prevent vote-selling. If you can show how you voted, selling your vote becomes easy. The coercer may also demand that you show some proof of whether you voted for their preferred candidate or not. So, the provability of votes would enable forms of coercion in return.

If anyone can find out who you voted for, they can easily influence your vote. Therefore, when implementing blockchain voting, we must ensure that votes remain completely anonymous and protected, without any third party influencing any voter.

So, how can blockchain maintain privacy protection and coercion resistance?

The Ethereum ecosystem has been experimenting with a system called MACI to implement a robust coercion-resistance voting system. Let’s examine it.

How the Ethereum Ecosystem is Trying to Address One of the Blockchain’s Stumbling Blocks

This system combines a blockchain, ZK-SNARKS, and a central actor guaranteeing coercion resistance. It has no power to influence any properties except coercion resistance. MACI is user-friendly as it allows users to participate by signing a message with their private key, encrypting the message to a public key provided by a central server, and publishing the encrypted, signed message to the blockchain.

The server then downloads the message from the blockchain, decrypts and processes it, and displays the results along with ZK-SNARK to ensure that the computation was performed correctly.

(Source)

Users cannot prove their participation; they can send a "key change" message to trick anyone trying to coerce them. The message will change their key from A to B and then send a "fake message" signed with A. The server will then reject the message, which no one will be able to find out.

The server has a trust requirement, although it applies only to privacy and coercion resistance protocols. The server cannot publish an incorrect result by censoring messages or computing incorrectly. In the future, multi-party computation can be used to decentralize the server, further improving privacy and ensuring coercion resistance.

Whether systems like MACI will completely address the problem of privacy and coercion resistance remains undetermined. In the meantime, it might be worth exploring alternative electoral voting systems to see if they are better than blockchain.

An Electoral Voting Alternative to Blockchain Voting

It wasn’t the blockchain nerds who came up with the idea of electoral voting. This concept of electronic voting existed outside the blockchain space, and for the past 20 years, cryptographers have been trying to solve different problems associated with it, some of which I have already mentioned above.

(Source)

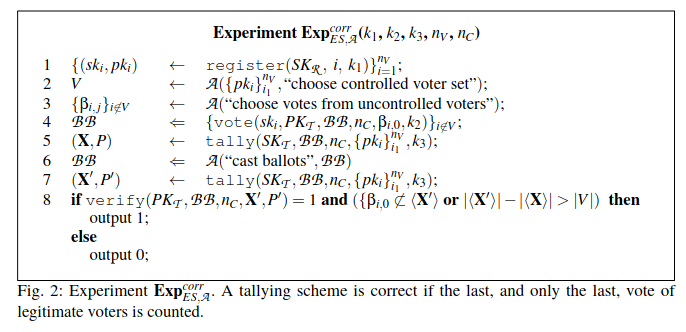

Many solutions have emerged so far, but a paper titled "Coercion-Resistant Electronic Elections" has been cited the most in this regard. The idea highlighted in this paper has undergone many iterations, and the protocol mentioned there uses a similar set of core techniques.

Here is what the paper states:

There is an agreed-upon set of people who will do the counting, and it is assumed that the majority of them are honest.

A private key is divided into multiple parts, each given to a different tallyer. A corresponding public key is published, which allows voters to publish their votes in an encrypted manner to the tallyer.

The talliers use their shares of the private key with an MPC protocol, a secure multi-party computation, to decrypt and verify the votes and calculate the results.

The calculation is done inside the MPC, and the talliers compute the final result without learning about the private key or the individual votes.

Encrypting votes provides privacy, and additional infrastructure like mix-nets makes it stronger. Two techniques are employed for coercion resistance.

In the first one:

The voter generates or receives a secret key during the registration phase (in this phase, talliers get access to the registered voter's public key). The public key is secretly shared among the talliers, and their MPC only counts a vote signed with the secret key.

No third party can access the secret key assigned to the voter. So, even if a voter is bribed or coerced, they can vote with the wrong secret key.

The wrong secret key will ensure that the vote is not counted during the tally. The secret key is used to prevent bribery or coercion.

Voters can even change their secret keys.

The second technique is that voters can cast multiple votes, with the second vote overriding the first. So, again, in a situation where they are threatened or bribed to vote for a preferred candidate, they can always fool the perpetrator by overriding their vote.

(Source)

So, what’s the problem?

The protocols mentioned above rely on an outside system, the bulletin board, to fulfill their security guarantees.

The bulletin board is a place where any voter can send a message, with a guarantee that:

- Everybody can read the bulletin board.

- Everyone can send a message to the bulletin board if it gets accepted.

Most of the coercion-resistant voting papers mention the existence of a bulletin board, but very few discuss how this can actually be implemented.

Here is the solution:

Using an existing blockchain is the most secure way to implement a bulletin board.

How Can We Implement a Blockchain Bulletin Board For Secure Electronic Voting

There have been many attempts to build a bulletin board before the arrival of blockchain. This paper from 2008 was one such attempt, and its trust model is a standard requirement that “K” of “N” servers must be honest (K = N;/2 is common)

Similarly, this literature review from 2021 highlights some of the pre-blockchain attempts at implementing bulletin boards and explores the use of blockchains for this role. The pre-blockchain solutions featured here also rely on the k-of-n trust model.

Even blockchain runs on the k-of-n trust model. It requires at least half of the miners or proof-of-stake validators to follow the protocol, resulting in a 51% attack. (A 51% attack, also called a majority attack, occurs when a group of miners or an entity controls more than 50% of the blockchain’s hashing power and then gains control over it.)

So, does this make blockchain a better system than a special-purpose bulletin board? Yes, because implementing a k-of-n trust model that can actually be trusted is hard, and blockchains are the only system that has successfully implemented it.

Suppose a government introduces a voting system and comes up with a list of 15 local organizations and universities running a special-purpose bulletin board. Will you be able to trust the credibility of these 15 organizations handpicked by the government from a list of 1000? What stops these chosen organizations from colluding with the government? It will be hard for voters to trust the credibility of this voting system.

On the other hand, public blockchains have permissionless economic consensus mechanisms (proof of stake or work) where anyone can participate. They also have an infrastructure of block explorers, exchanges, and other watching nodes to continuously verify in real time that nothing suspicious is going on.

A foolproof voting system won’t rely solely on blockchains. It will also use cryptography, such as zero-knowledge proofs, to guarantee correctness and secure multi-party computation to ensure coercion resistance.

So, blockchain bulletin boards will play an essential role in the security model of the electronic voting system because, without them, there will be no way to maintain coercion resistance, even if other safety protocols around the voting process remain.

With that, we might have come full circle with blockchain voting, where blockchain might be necessary in an alternate system to address the very issue that threatened its use in the first place.

Hardware Security Concerns with Implementing Blockchain Voting Systems

While blockchain-based electoral voting may be promising, it is still under development. Hardware and device-based security concerns could also hinder its wide-scale adoption.

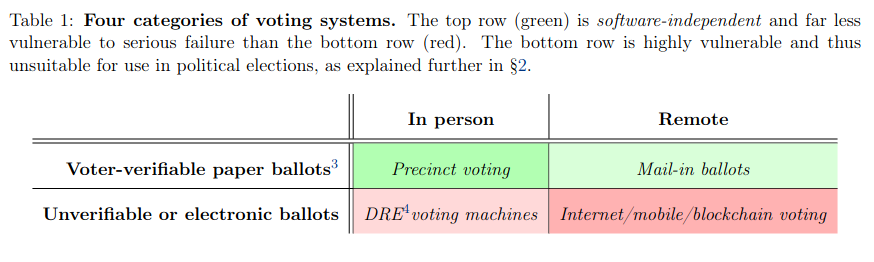

A paper from MIT declared that any form of paperless voting is fundamentally risky to implement.

(Source)

The authors' genuine concern is ensuring people’s devices are properly secured. They are not concerned with the voting system’s secure hardware, as zero-knowledge proofs can mitigate risks.

Consumer devices getting hacked is nothing new. For example, in June 2011, the Bitcointalk member “allinvain” lost 25,000 BTC (worth $500,000) after an intruder gained direct access to his computer. The attacker could access allinvain’s wallet.dat file and quickly empty the entire wallet. They could do it either by sending a transaction from allinvain’s computer or by uploading the wallet.dat file and emptying it on his machine.

But despite these disasters, computer security has been improving slowly and steadily. It’s difficult to attack a system because the attacker will have to find bugs in multiple subsystems instead of a single hole in a large, complex piece of code.

Trusted hardware has played a significant role in all of this. Some of the new blockchain smartphones put a security-focused operating system on the trusted hardware chip, thus allowing high-security-demanding applications to stay separate from the other applications.

Single applications like cryptocurrency wallets and voting systems are much simpler and have less room for error than an entire consumer operating system. Tools like trusted hardware benefit from their ability to isolate the simple from the complex and possibly broken, and these tools are having some success. The risk will decrease over time.

Note: Trusted hardware should not wholly replace the security protection. It should only augment it further.

How ‘Risky Crypto’ can lead to ‘Secure Elections'

Cryptocurrencies, and blockchains by extension, have gained somewhat of a negative connotation in the minds of the average Joe. Convincing the populace to adopt blockchain for elections can, therefore, be a challenge.

However, I would like to argue that the crypto space can actually be very helpful when researching and implementing blockchain elections. The world of cryptocurrencies and NFTs is highly competitive and full to the brim, with hackers, scammers, and fraudsters snooping around for any opportunity to exploit the systems to make an extra buck.

That means any and every crypto system, once launched to the public, will undoubtedly be stress tested for security and stability, having to survive constant attacks by these bad players. Theoretically, we can test out electoral systems in the crypto space first, where bad players are equally motivated to break the systems, but the stakes are much lower. If a system can survive in the crypto space, it can survive in the real world.

Ultimately, blockchain will make voting more efficient, allowing people to participate more often.

Parting Thoughts

In essence, we discussed Blockchina’s applicability within the electoral system. Here is a quick recap:

- Blockchain-based voting has been implemented in a few small countries and some American state elections, and its reception has been mixed.

- To make voting more secure, the voting process has four essential security requirements: censorship resistance, correctness, coercion resistance, and privacy.

- Blockchains are an excellent system for censorship resistance and correctness, but their current implementations may lack privacy and coercion resistance.

- Encryption of votes can add privacy on a blockchain, and zero-knowledge proofs can ensure correctness in results despite observers being unable to add up votes directly due to encryption.

- Multi-party computation may provide coercion resistance if combined with a process where users can interact with the system multiple times, in which the first interaction invalidates the second, or vice versa.

- In simple words, blockchain voting still faces some significant technical challenges. Still, theoretical solutions for these certainly exist, and new research continues to shed light on better ways of implementing blockchain.

- With blockchain-based electoral voting, there is also the issue of securing hardware and building a system robust enough to defend against attackers. Borrowing a trick or two from the crypto space can help here.

For now, any form of blockchain voting should strictly remain confined to small experiments only. The current technology is not secure enough to rely solely on computers for everything. However, the security aspect will keep improving, and in the future, there will be a big incentive to use electronic voting systems for elections.